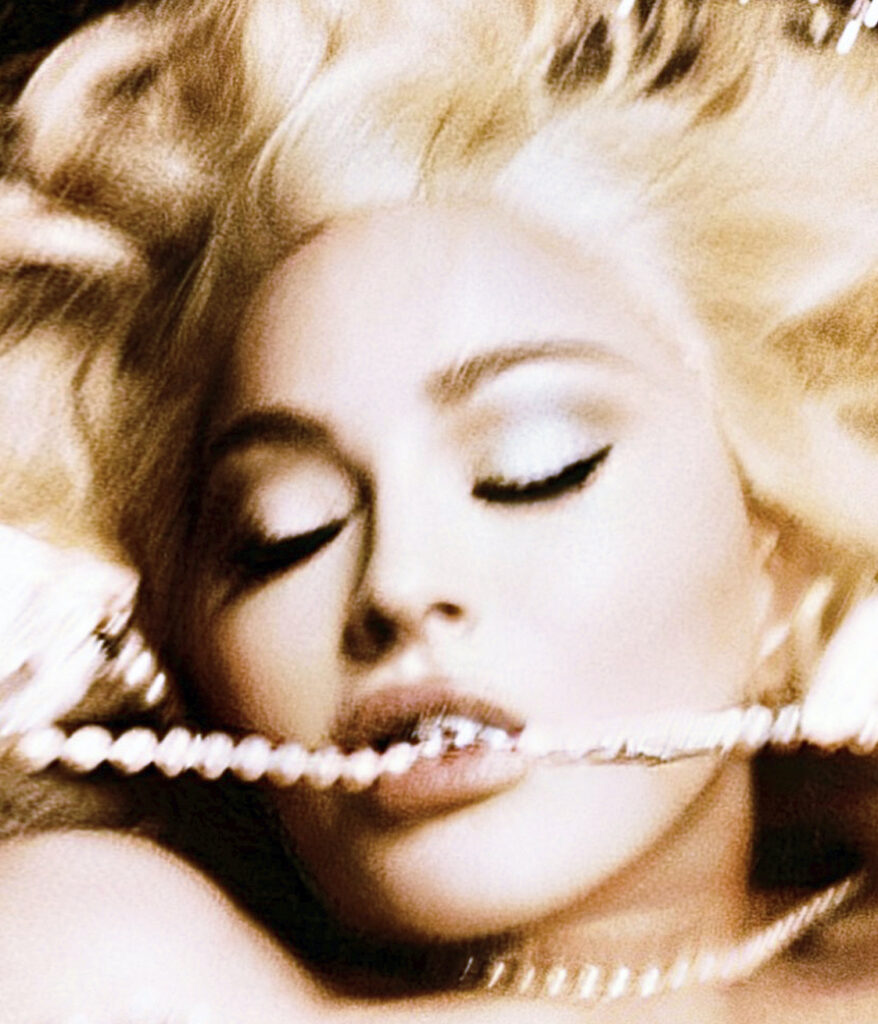

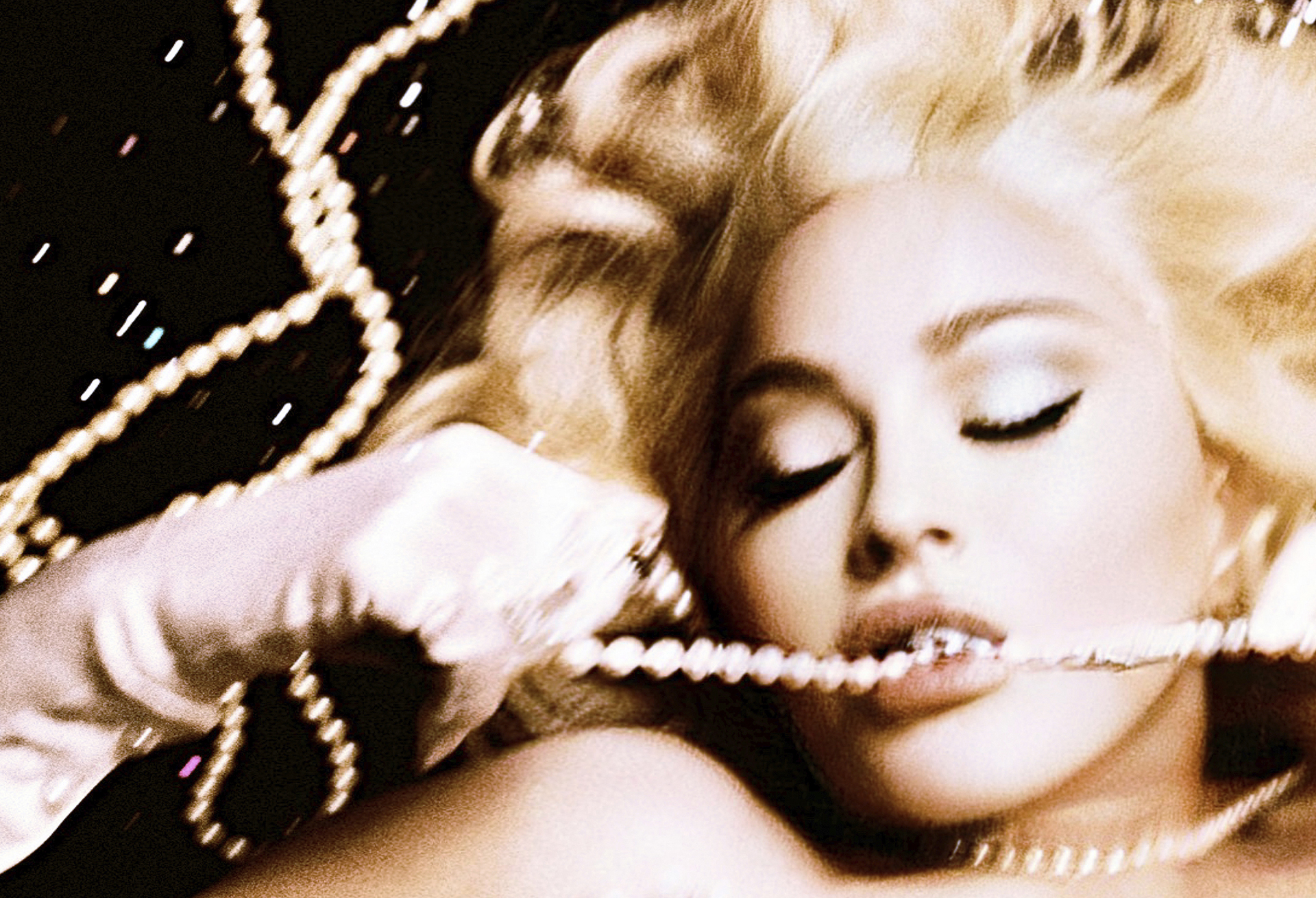

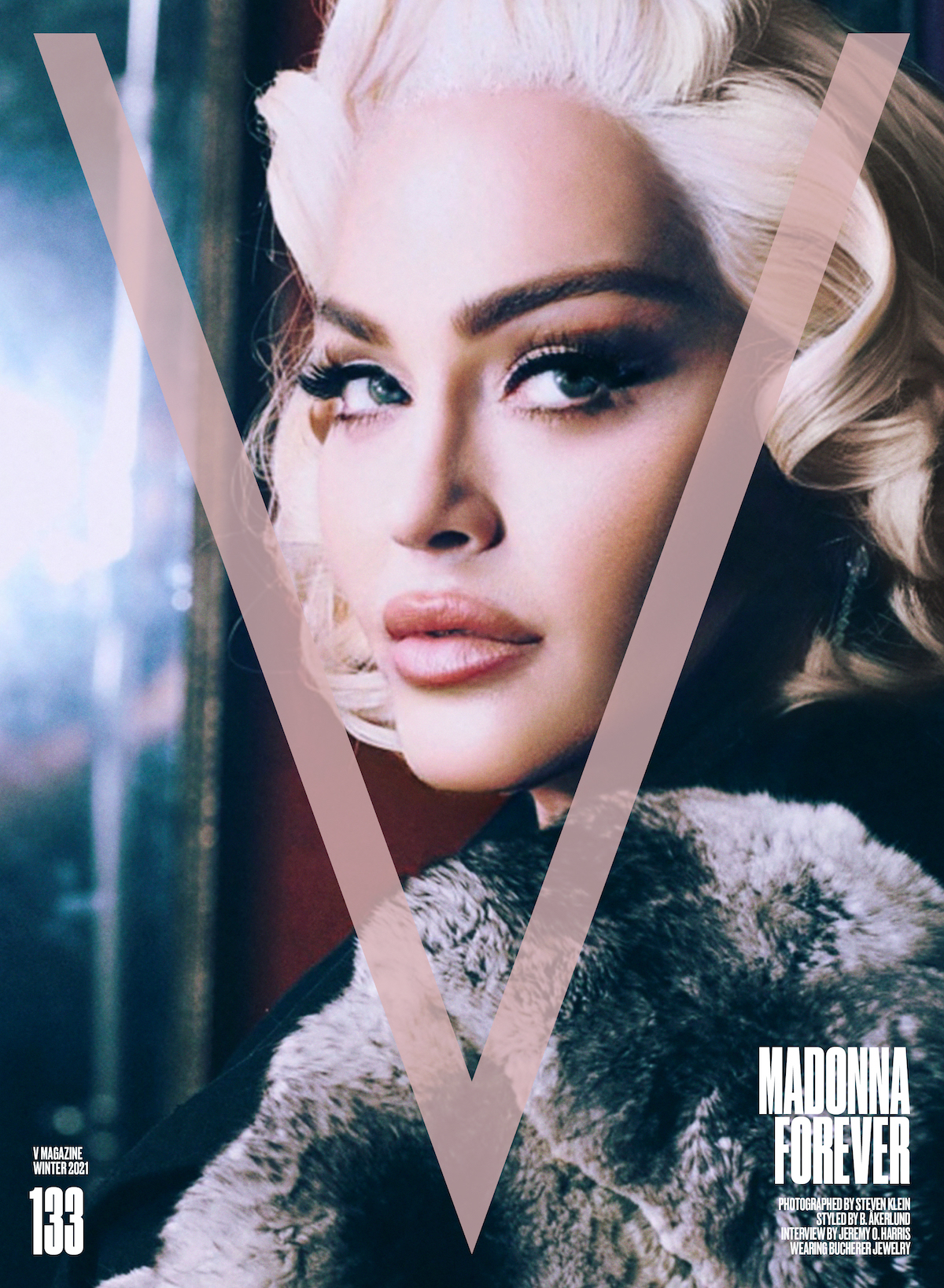

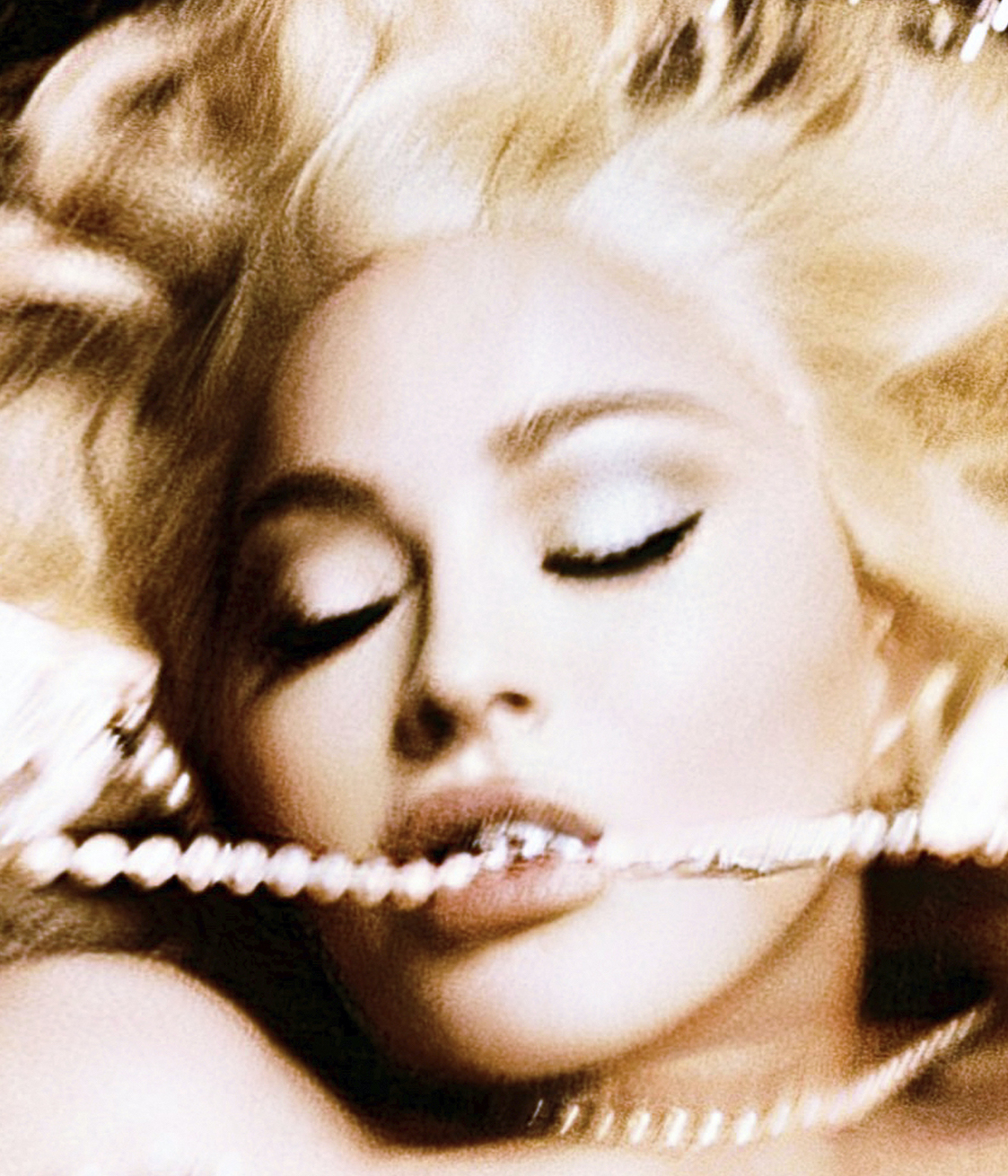

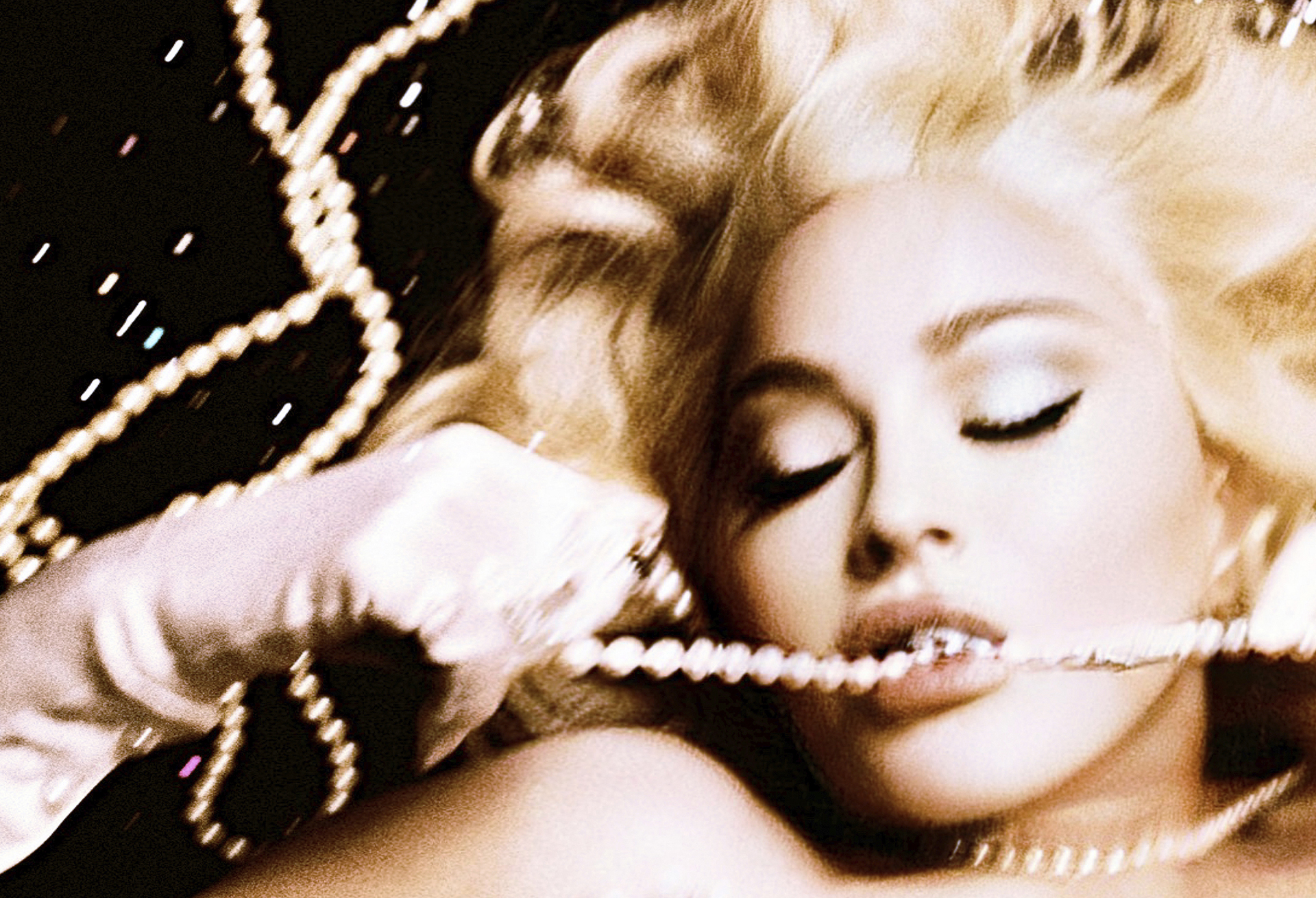

“This photo essay was inspired by a shoot that Marilyn Monroe did with photographer Bert Stern titled “The Last Sitting.” They shot at the Bel Air hotel in 1962, before she passed away. What was supposed to be a three-hour sitting, turned into a three-day whirlwind, working night and day. Drinking, laughing, shooting photos, editing, sleeping, and then taking more photos–a private affair between two artists which rarely happens anymore. We were not interested in recreating the images exactly but more importantly, we wanted to explore the relationship between photographer and subject. Both the friendship and the artistic process, and how art can imitate life and vice versa. When I sent Madonna the photos she was really taken by the incandescent fragility of Marilyn at that moment in her life. We decided to find a hotel suite and try to capture the liaison between a star and the camera, the mystery, and magic of this creative collaboration. We hope we have done justice to the great work of Bert Stern and Marilyn Monroe.”

Steven Klein

Madonna and Jeremy O. Harris are friends and collaborators who share a common ethos: a desire to make us look differently at the world. Their epochal work—in the respective fields of music and theater—tests boundaries, asks questions, and is, to quote a 2015 Madonna song, always unapologetic. On a September evening in L.A., the pair met up to discuss Madonna’s new Madame X film, the power of art to create change, and why, more than ever, bold storytelling is crucial.

Jeremy O. Harris: One of my first questions I wanted to ask you is about one of the quotes that opens Madame X which is “Artist’s are here to disturb the peace.” I wanted to know for you, where is peace right now? There’s a global pandemic, there’s billionaires wrecking the economy and every sector of our world. Where do you think there’s peace to disturb?

Madonna: It’s interesting because peace is subjective. The way people think about the pandemic, for instance, that the vaccination is the only answer or the polarization of thinking you’re either on this side or the other. There’s no debate, there’s no discussion. That’s something I want to disturb. I want to disturb the fact that we’re not encouraged to discuss it. I believe that our job is to disturb the status quo. The censoring that’s going on in the world right now, that’s pretty frightening. No one’s allowed to speak their mind right now. No one’s allowed to say what they really think about things for fear of being canceled, cancel culture. In cancel culture, disturbing the peace is probably an act of treason. We could start right there, and then we can just talk about our work as artists. The work that you do is very disturbing, but not in a bad way. When I watched Slave Play my mind was so fucking blown for so many reasons. You talk about things that aren’t encouraged to be spoken about. You deal with topics that are not discussed in everyday society, even though we’re supposed to be so woke. That, to me, and what you do is exactly what James Baldwin is talking about. Have you heard his speech about an artist’s integrity? It’s so awe-inspiring.

JOH: Did you ever get to meet him?

M: No. God, I wish I would have.

JOH: I feel like he would have had a great time with you.

M: I think we would’ve gotten along really well. I worshiped Giovanni’s Room; that’s how I discovered who he was. But then I got into reading his other teachings, listening to his speeches, following his path through the civil rights movement, and also relationships with people and artists.

JOH: It’s so funny you brought up cancel culture. Because my hot take about cancel culture is that I don’t think that it’s as frightening as some people feel it is.

M: The thing is the quieter you get, the more fearful you get, the more dangerous anything is. We’re giving it power by shutting the fuck up completely.

JOH: My only frustration with the ideas around cancel culture, I do see this feeling from many young artists that there is a right way to tell a story or a right way to create. And a lot of those right ways involve not provoking or causing any ripples amongst people. And what that is articulating, is that to see people, to truly see people, is to cause ripples, which is what you’ve done the entire time. When you poke at something that people say, “don’t touch that, never touch that,” it makes people feel things when you do touch it. And you’ve been doing that since the very beginning.

M: Ever since I stuck my finger in the cigarette lighter in the car, I kept pushing it and playing with it. Every kid does it and your parents tell you, “don’t touch it, you’re going to burn your finger.” All you have to do is tell me that, and I need to touch it.

JOH: What happened when you touched it and burned your finger?

M: My father just said, “That’s what you get.” No sympathy.

JOH: What did you feel about it? Did you feel empowered that you had done this thing they told you not to do? Or did you feel the burn?

M: I felt the burn. I wanted to cry, but I clenched my teeth. I choked back tears and I just said, “I will not show any pain. I’m just going to get through it. I’m going to prove to my father that it’s okay to get burned sometimes.”

JOH: Whenever I’ve been asked to teach, they tell me, “How do you write a good play or a play that people care about?” I say, “I can’t tell you how to do that.” All I can do is tell you to write toward failure. To write off the cliff. So that maybe it won’t work. Because the chance to get burned is the reason to do the thing. Do you feel like that’s what Madame X was for you?

M: Well, first of all, everyone told me not to do it because it was too ambitious. Because there were too many people on the stage. I was trying to tell too many stories. I was trying to share too much of the things that I love in one space and time. Because the overhead was going to be so big and, in a theater that only holds 1500- 2000 people every night, I was gonna barely make any money at the end of the day, especially with union rules. If I was half an hour late, or even when we were in pre-production rehearsals. I didn’t know this, but the union rules in theaters are so crazy and their hours are nine-to-five. And I’m like, “Who works those hours?” And I said, “Can’t they just shift the hours from four to midnight?” That’s so much more conducive to our mentality—when we work, when we’re alive. And they refused. And so anything after five is overtime. So you can imagine the bills I incurred just in rehearsals because we rehearsed every night till three in the morning. We had to and we still weren’t ready when we were open. I started off with 16 people, and then I decided to bring in 36! “I can’t just have eight Batukadeiras!” Even the ones I had were still only half. Then I had to bring in all the musicians from Portugal. Then I had all the dancers. I was excessive because I needed all of those people to tell my story. From the gate, my manager said, “This is going to be a disaster for you because you’re not gonna make any money.” And of course, he would ask, “Why are you killing yourself? You don’t have to work so hard. Nobody works this hard. If you just do one-quarter of what you’re doing, it will still be more than everybody else.” And I say, “Yeah, but that’s not how I work.” Everything in the show had to be the most amazing thing that I could possibly do. Even if I fall off a cliff, as you say, it might not work. But how do you know these things until you try them? And some things didn’t work in the beginning and we got rid of them. But that’s the beauty of theater, that you can try things out in front of an audience. Talking to people when people can’t see you, to me that’s writing to failure. No one can see my face, they can only see me getting my shoes changed. And I thought that was pretty risky. But in the end, I loved it. I loved the perversity of it.

JOH: One of the lines you have that I’ve thought about a lot is, “The most radical thing I ever did was to stick around.” And when I hear that, is that the most radical thing you can do? Or would it have been really radical if you just disappeared, and just never shown back up after Ray of Light.

M: You mean die like everybody else?

JOH: Well, not die but just go into hiding, like J.D. Salinger in a forest in the woods.

M: That could have been, but I didn’t want to make homeopathic medicine in the woods like J.D. Salinger did.

JOH: For you performing is to fail, working to death, something that feels deeply radical. Because, outside of Yvonne Rainer and Martha Graham, I can’t think of any women after 60 performing live for people consistently. And even those women didn’t perform at the level that you’re performing. Does that scare you at all?

M: I don’t even think about my age, to tell you the truth. I just keep going. Even when I performed almost my entire tour in agony, I had no cartilage left in my right hip, and everyone kept saying, “You gotta stop, you gotta stop.” I said, “I will not stop. I will go until the wheels fall off.” And it was COVID that shut us down in Paris when we still had 10 days left of shows and I was going to keep going. I didn’t care how much it hurt. But to your point, I don’t ever think about the limitations of time and when I should be stopping. I only think about it when extremely ignorant people say to me, “Don’t you think you’ve earned the right to just sit back and enjoy all of your success and all things that you’ve achieved and retire?” Not retire, no one would dare say that word to me. I say to them, “Wait a second. Why do you think I do what I do?” Why do you do what you do? Do you have a stop date for yourself?

JOH: I don’t know that I do.

M: I think we’ll just stop when we don’t have any fucking ideas, when we don’t feel inspired anymore.

JOH: You’re not doing it for vanity or glamour?

M: I mean, I hope I look cute when I’m doing it. I’m an extremely vain person. I also quote James Baldwin at the end of one of my songs in act three [of the Madame X concert and film]—I say that, “We’re not here to be popular, we’re here to be free.” And that is a very liberating thing to get your head around and to say, “I don’t care, I’m just going to do it.” So I don’t think about stopping. I could have done a stadium tour, greatest hits, and made a billion dollars.

JOH: You’re the most successful touring musician of all time, male or female.

M: Right. So I could have done that, but there would have been no joy in it for me. I just don’t like the idea of repeating myself. I don’t like the idea of giving the people what they want. I’ll give them a little bit of what they want, and then I’m going to give them some other stuff.

JOH: Yeah, like an introduction to African musicians they never heard of, and an entire band from Portugal that they had no idea they were going to be witnessing.

M: Yeah, and also some incredible dancing, contemporary dancing, which people are really not exposed to anymore, which is what I grew up on. Martha Graham was my life. And I moved to New York to be a contemporary dancer. That world is a world that people don’t really know anymore. The kind of dancing people know is TikTok dancing or hip-hop. No diss to that culture either. It’s just not the same.

JOH: It’s rarified.

M: It’s rarified because it requires skill, it requires study, years of study and Martha Graham, she performed in her ‘70s. I first met her when I was studying at her school. Meeting her for the first time I was starstruck, “Oh my God, my heroine.” The second time we hung out she invited me to dinner at her house. By then, I was already successful and not a dancer anymore. It was really cool to sit at the table with her and feel like she saw me as her equal. What’s really important to me when I do anything that I do is to bring things that I’ve discovered that inspired me, to the world. Things that have blown my mind, or really lifted my spirits, or informed me in a spiritual way.

JOH: Like when you brought contemporary dance or vogue to what you were doing on the world stage?

M: Yeah, when I saw voguing for the first time at The Sound Factory, it was like, Wait, what the fuck is that!! That’s some crazy shit.

JOH: When you sat across from Martha Graham at that dinner where you guys were seeing each other, like equals, what did you talk about?

M: We talked about her collaborations with this Japanese artist named Noguchi. He did a lot of sculptures for her, for her live shows. And she had Japanese sculptures everywhere. She was very influenced by Japanese culture. And the composer, Aaron Copland. She always worked with him. She talked about working with people, with dancers who are not afraid to take risks, destroy their bodies, bust up their knees. Her choreography is crazy. It’s painful, it’s sexual, it’s angst-ridden, it’s gut-wrenching. We talked about the importance of finding people like that to collaborate with as an artist. I remembered that later on. I need to find my gang, my people who work like I work. We talked about that and we talked about her calling me “Madame X,” when she first met me.

JOH: Because your outfits were so lascivious at school?

M: Well, it was a couple of things. I’m the girl that sticks her finger in the lighter in the car. I couldn’t just wear a leotard and tights. Cause I thought, “Well, wait a second.” This is modern dance. This is not ballet where everybody’s very rigid and uniform and Martha Graham in her heyday when she was young and traveling around the United States: she’s the one who threw off the corsets and the point shoes and the girls were dancing on stage with no bras and their boobs were bouncing around. And it was considered to be very sexual and controversial. And I thought, “Wait, how could she be that person and be so strict about the way we are dressed in class.” So I decided to push the envelope. I cut my leotard down the front to my pubic bone and then fastened it back up with tiny gold safety pins and I got her attention. But the other thing was I needed to make money on the side because, if you’re a contemporary dancer, you never make any money. I was doing things like going to hair salons and letting people experiment on my hair, you know, cornrow it and then take out half of it and shave one side of my head. I was constantly showing up to class as part of someone else’s experiment.

JOH: That’s Madame X!

M: She kept looking at me. Sometimes she would crack the door in her office and she would watch students going past. And sometimes she would poke her head into class. I think her point was every time she’d see me, I had a different look and, so when I got called into her office, she said, “I don’t recognize you. Every time I see you, you’re like a spy.” I thought, “That’s cool.” So inadvertently, I was already creating this idea of creating personas and the idea that we can embody so many different people and it’s still art and it’s still theater and it’s still storytelling. That’s what I was talking to you about. Why do we do what we do? And I think that’s what James Baldwin is saying when he says we’re poets, we’re storytellers but how do we tell our stories? We tell them through music, we tell them through dance. We tell them through our words, whether we’re writing a screenplay or a play, we tell them through fine art. We can even be storytellers as parents. People need to stop thinking in such a limited way. When I say, “Madame X is a teacher, a nun, a housewife” I mean [that] there’s a place for poetry in all of those things.

JOH: Has there been any thing that you’ve heard or seen recently that are cute?

M: I mean, the only thing that I’ve heard recently that has inspired me is Kanye’s record Donda. There are very few artists that are working toward failure. And I feel like he is.

JOH: He’s staring at an abyss right now.

M: Totally. I can’t say that I agree with all of his politics and the way that he thinks of women, or unmarried people having sex, or the gay community. But his work is on the razor’s edge, and it’s inspiring and it’s rare. Everybody was waiting so long for his record to come out and then finally when it came out, everybody else’s record came out, too. And he still stood out.

JOH: Yeah. But, did you not feel a certain type of way that he even invited DaBaby?

M: I was conflicted about that, but, like I said, I have to pay attention to the message, not the messenger. That’s important. Listen to the teachings. Don’t get caught up in the teacher, what the teacher’s doing. I mean, if you want to get down to dissect the character, look at the way Martin Luther King lived his life. You know, he was a Christian, God-fearing man preaching about morals and values and family. And he had mistresses everywhere. And definitely, not living up to the image that he was presenting about himself, but does that take away from what he did for the world and how he sacrificed his life and how he was willing to work to failure, the ultimate failure, which is death by assassination? No. And, and I’m really disgusted by….did you see the documentary that just came out about him? It’s called MLK/FBI. J. Edgar Hoover, and even the Kennedys, ultimately were after his ass, trying to bring him down as a communist by exposing him as a womanizer. They taped him everywhere and those tapes are going to be released in seven years. I don’t want to hear them.

JOH: Yeah. Five movies and TV shows are coming out about those tapes. Something I think is really cute is your boyfriend, who I think is gorgeous. He took my breath away when we had dinner that time. I wonder, what did you feel having to watch him die at the beginning of Madame X? He was the opening sequence of the show.

M: Well, that’s what made me fall in love with him: his commitment to what he was doing. And also that he was embodying and personifying both Malcolm X and the writing of James Baldwin. And I loved that. He died before I came on stage every night. There was something very poetic about it.

JOH: Because I think that when I see that I say, “Wow she’s really going there” and putting something like that on stage. The opening image of your play, much like my play, feels like such a theatrical event. The opening image is so weighted. And so historicized that it sets a strong tone that you have to follow through with…

M: Follow through with gun control or “God Control.” Yeah.

JOH: Were you worried about that? How many notes did you go through to get to the version we see now?

M: We rehearsed for 10 weeks. The costumes had a big part to play in it, the video projections, the Batukadeiras on the steps dressed as slaves during Antebellum times, juxtaposed against the marches on the street, Black Lives Matter. Everything was so potent with meaning and it had to be followed by that. I didn’t have a lack of ideas, and then moving from that to religion and challenging the church, which is what “Dark Ballet” was. And then challenging sexuality with “Human Nature.” And everybody putting me in that hole on stage, that circle and keeping me there and bringing my eight-year-old daughters on stage saying, “I’m not your bitch”—that was so dope. I had to write a check with my mouth that my ass could cash. You feel me?

JOH: I feel you hard. I love that you brought your daughters on stage. I love that you have the Best Dad Ever placard here on your desk. When I saw Madame X for the first time [it was] after I had dinner at your house and met all of your kids, which was such an amazing moment for me, because it’s very easy to understand Madonna as a pop star. It’s easy to understand Madonna as a controversial figure, but it’s hard to understand Madonna as a mother. I also think it’s even harder to understand Madonna as a mother of Black children. Because transracial adoption is something that people still don’t really understand. Something that’s not really talked about. And I felt so honored to be able to witness how great of a mother you were with your kids and how great of a mother to Black children you are and how much there was an embrace and celebration of culture in your household.

M: I think when you start off in your life with a very big slap in the face you have a different view of the world. You just do. The slaps are going to come anyways to everybody. Everyone’s going to get slapped. And probably several times, especially if you are an artist working toward failure, because that’s the nature of the game and it’s the getting back up, falling, and then getting back up. There’s a line in my script, when my mother dies, I get back up and I keep going. And [when] all my friends died of AIDS, I get back up and I keep going, Basquiat dies, and I get back up and I keep going. This stranger rapes me with a knife to my throat. I get back up and I keep going. My ex-husband betrays me. I get back up and I keep going. My brother betrays me, I get back up and I keep going. Either you have that mentality that you get back up and keep going, or you sit around, thinking about what people are thinking about you all the time. The challenges that I’ve had, since I was a child, are the things that make me realize how precious life is and leaning over and kissing my mother’s lips in a coffin, made me think…in the blink of an eye, everything could change. I’m not wasting one second of it, and fuck anybody who tries to get in my way.

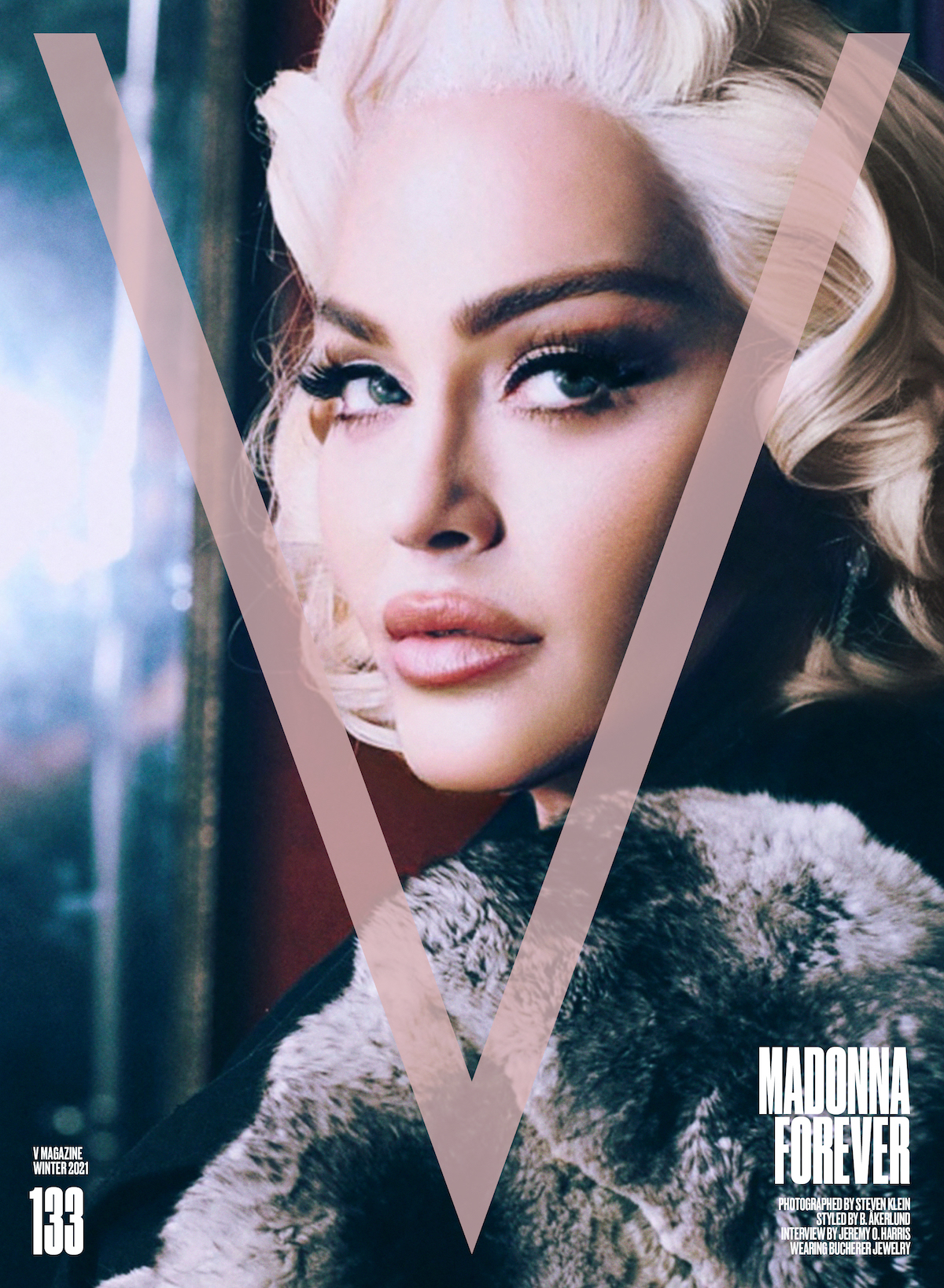

Watch the ‘Private Affair’ starring Madonna by Steven Klein for V133, below:

This cover story appears in V133: now available for purchase!

Discover More